The Birth of Soft Torture

Rebecca Lemov - In 1949, Cardinal Jószef Mindszenty appeared before the world's cameras to mumble his confession to treasonous crimes against the Hungarian church and state. For resisting communism, the World War II hero had been subjected for 39 days to sleep deprivation and humiliation, alternating with long hours of interrogation, by Russian-trained Hungarian police.

His staged confession riveted the Central Intelligence Agency, which theorized in a security memorandum that Soviet-trained experts were controlling Mindszenty by "some unknown force." If the Communists had interrogation weapons that were evidently more subtle and effective than brute physical torture, the CIA decided, then it needed such weapons, too.

Months later, the agency began a program to explore "avenues to the control of human behavior." During the next decade and a half, CIA experts honed the use of "chemical and biological materials capable of producing human behavioral and physiological changes" according to a retrospective CIA catalog written in 1963. And thus soft torture in the United States was born.

In short order, CIA experts attempted to induce Mindszenty-like effects. An interrogation team consisting of a psychiatrist, a lie-detector expert, and a hypnotist went to work using combinations of the depressant Sodium Amytal and certain stimulants. Tests on four suspected double agents in Tokyo in July 1950 and on 25 North Korean prisoners of war three months later yielded more noteworthy results. (Relevant CIA documents do not specify exactly what, but reports later claimed that the special interrogation teams could hold a subject in a "controlled state" for a long period.)

Meanwhile, the CIA opened the door to pre-emptive psychosurgery: In a doctor's office in Washington, D.C., one unfortunate man, his name deleted from documents, was lobotomized against his will during an interrogation. By the mid-to-late 1950s, experiments using "black techniques," as the agency called them, moved to prisons, hospitals, and other field-testing sites with funding and encouragement from the CIA's Technology and Science Directorate.

Dr. Ewen Cameron had been pioneering a technique he called "psychic driving."

One of the most extreme 1950s experiments that the CIA sponsored was conducted at a McGill University hospital, where the world-renowned psychiatrist Dr. Ewen Cameron had been pioneering a technique he called "psychic driving." Dr. Cameron was widely considered the most able psychiatrist in Canada—his honors included the presidency of the World Psychiatric Association—and his patients were referred to him from all over. A disaffected housewife, a rebellious youth, a struggling starlet, and the wife of a Canadian member of Parliament were a few of the more than 100 patients who became uninformed, nonconsenting experimental subjects. Many were diagnosed as schizophrenic (a diagnosis since contested in many of the cases).

Cameron's goal was to wipe out the stable "self," eliminating deep-seated psychological problems in order to rebuild it. He grandiosely hoped to transform human existence by opening a new gateway to the understanding of consciousness. The CIA wanted to know what his experiments suggested about interrogating people with the help of sensory deprivation, environmental manipulation, and psychic disorientation.

Cameron's technique was to expose a patient to tape-recorded messages or sounds that were played back or repeated for long periods. The goal was a condition Cameron dubbed "penetration": The patient experienced an escalating state of distress that often caused him or her to reveal long-buried past experiences or disturbing events. At that point, the doctor would offer "healing" suggestions. Frequently, his patients didn't want to listen and would attack their analyst or try to leave the room. In the 1956 American Journal of Psychiatry, Cameron explained that he broke down their resistance by continually repeating his message using "pillow and ceiling microphones" and different voices; by imposing periods of prolonged sleep; and by giving patients drugs like Sodium Amytal, Desoxyn, and LSD-25, which "disorganized" thought patterns.

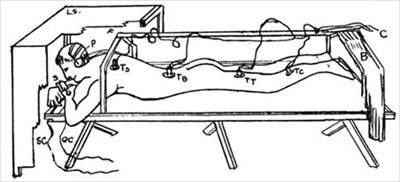

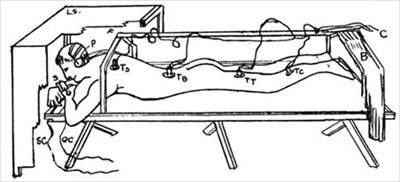

To further disorganize his patients, Cameron isolated them in a sensory deprivation chamber. In a dark room, a patient would sit in silence with his eyes covered with goggles, prevented "from touching his body—thus interfering with his self image." Finally "attempts were made to cut down on his expressive output"—he was restrained or bandaged so he could not scream. Cameron combined these tactics with extended periods of forced listening to taped messages for up to 20 hours per day, for 10 or 15 days at a stretch.

In 1958 and 1959, Cameron went further. With new CIA money behind him, he tried to completely "depattern" 53 patients by combining psychic driving with electroshock therapy and a long-term, drug-induced coma. At the most intensive stage of the treatment, many subjects were no longer able to perform even basic functions. They needed training to eat, use the toilet, or speak. Once the doctor allowed the drugs to wear off and ceased shock treatments, patients slowly relearned how to take care of themselves—and their pretreatment symptoms were said to have disappeared.

So had much of their personalities. Patients emerged from Cameron's ward walking differently, talking differently, acting differently. Wives were more docile, daughters less inclined to histrionics, sons better-behaved. Most had no memory of their treatment or of their previous lives. Sometimes, they forgot they had children. At first, they were grateful to their doctor for his help. Several Cameron patients, however, later said they had severe recurrences of their pretreatment problems and traumatic memories of the treatment itself and together sued the doctor as well as the U.S. and Canadian governments. Their case was quietly settled out of court.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, CIA experts thought they understood the techniques necessary for "breaking" a person. Under a strict regime of behavioral conditioning, "the possibility of resistance over a very long period may be vanishingly small," several researchers concluded in an analysis used in the CIA's 1963 manual Counterintelligence Interrogation. At the agency, pressure increased to field-test coercive interrogation tools. The task, as CIA second-in-command Richard Helms urged, was to test the agency's techniques on "normal" people.

At times, this imperative made the agency reckless. As part of the now notorious MK-ULTRA program—"one of the seamiest episodes in American intelligence," according to journalist Seymour Hersh—the CIA set up a safe house in San Francisco where its agents could observe the effects of various drug combinations on human behavior. They were in search of a "truth serum" and thought LSD might be it. Prostitutes were hired to bring unwitting johns back to the house, where the women slipped acid and other strong psychoactive substances into the men's drinks. From behind a one-way mirror, investigators watched, notebooks and martinis in hand.

Sometimes the men took the drugs and managed to carry on. Sometimes they babbled or cried. An internal CIA review condemned these high jinks in 1963, but Congress didn't investigate them until 1977, after a post-Watergate crisis of confidence in the agency.

At least officially, the CIA ended its behavioral science program in the mid-1960s, before scientists and operatives achieved total control over a subject. "All experiments beyond a certain point always failed," an operative veteran of the program said, "because the subject jerked himself back for some reason or the subject got amnesiac or catatonic." In other words, you could create a vegetable or a zombie, but not a robot who would obey you against his will. Still, the CIA had gained reliable information about how to derange and disorient a person who was reluctant to cooperate. An enemy could quickly be made into a confused and desperate human being.

His staged confession riveted the Central Intelligence Agency, which theorized in a security memorandum that Soviet-trained experts were controlling Mindszenty by "some unknown force." If the Communists had interrogation weapons that were evidently more subtle and effective than brute physical torture, the CIA decided, then it needed such weapons, too.

Months later, the agency began a program to explore "avenues to the control of human behavior." During the next decade and a half, CIA experts honed the use of "chemical and biological materials capable of producing human behavioral and physiological changes" according to a retrospective CIA catalog written in 1963. And thus soft torture in the United States was born.

In short order, CIA experts attempted to induce Mindszenty-like effects. An interrogation team consisting of a psychiatrist, a lie-detector expert, and a hypnotist went to work using combinations of the depressant Sodium Amytal and certain stimulants. Tests on four suspected double agents in Tokyo in July 1950 and on 25 North Korean prisoners of war three months later yielded more noteworthy results. (Relevant CIA documents do not specify exactly what, but reports later claimed that the special interrogation teams could hold a subject in a "controlled state" for a long period.)

Meanwhile, the CIA opened the door to pre-emptive psychosurgery: In a doctor's office in Washington, D.C., one unfortunate man, his name deleted from documents, was lobotomized against his will during an interrogation. By the mid-to-late 1950s, experiments using "black techniques," as the agency called them, moved to prisons, hospitals, and other field-testing sites with funding and encouragement from the CIA's Technology and Science Directorate.

Dr. Ewen Cameron had been pioneering a technique he called "psychic driving."

One of the most extreme 1950s experiments that the CIA sponsored was conducted at a McGill University hospital, where the world-renowned psychiatrist Dr. Ewen Cameron had been pioneering a technique he called "psychic driving." Dr. Cameron was widely considered the most able psychiatrist in Canada—his honors included the presidency of the World Psychiatric Association—and his patients were referred to him from all over. A disaffected housewife, a rebellious youth, a struggling starlet, and the wife of a Canadian member of Parliament were a few of the more than 100 patients who became uninformed, nonconsenting experimental subjects. Many were diagnosed as schizophrenic (a diagnosis since contested in many of the cases).

Cameron's goal was to wipe out the stable "self," eliminating deep-seated psychological problems in order to rebuild it. He grandiosely hoped to transform human existence by opening a new gateway to the understanding of consciousness. The CIA wanted to know what his experiments suggested about interrogating people with the help of sensory deprivation, environmental manipulation, and psychic disorientation.

Cameron's technique was to expose a patient to tape-recorded messages or sounds that were played back or repeated for long periods. The goal was a condition Cameron dubbed "penetration": The patient experienced an escalating state of distress that often caused him or her to reveal long-buried past experiences or disturbing events. At that point, the doctor would offer "healing" suggestions. Frequently, his patients didn't want to listen and would attack their analyst or try to leave the room. In the 1956 American Journal of Psychiatry, Cameron explained that he broke down their resistance by continually repeating his message using "pillow and ceiling microphones" and different voices; by imposing periods of prolonged sleep; and by giving patients drugs like Sodium Amytal, Desoxyn, and LSD-25, which "disorganized" thought patterns.

To further disorganize his patients, Cameron isolated them in a sensory deprivation chamber. In a dark room, a patient would sit in silence with his eyes covered with goggles, prevented "from touching his body—thus interfering with his self image." Finally "attempts were made to cut down on his expressive output"—he was restrained or bandaged so he could not scream. Cameron combined these tactics with extended periods of forced listening to taped messages for up to 20 hours per day, for 10 or 15 days at a stretch.

In 1958 and 1959, Cameron went further. With new CIA money behind him, he tried to completely "depattern" 53 patients by combining psychic driving with electroshock therapy and a long-term, drug-induced coma. At the most intensive stage of the treatment, many subjects were no longer able to perform even basic functions. They needed training to eat, use the toilet, or speak. Once the doctor allowed the drugs to wear off and ceased shock treatments, patients slowly relearned how to take care of themselves—and their pretreatment symptoms were said to have disappeared.

So had much of their personalities. Patients emerged from Cameron's ward walking differently, talking differently, acting differently. Wives were more docile, daughters less inclined to histrionics, sons better-behaved. Most had no memory of their treatment or of their previous lives. Sometimes, they forgot they had children. At first, they were grateful to their doctor for his help. Several Cameron patients, however, later said they had severe recurrences of their pretreatment problems and traumatic memories of the treatment itself and together sued the doctor as well as the U.S. and Canadian governments. Their case was quietly settled out of court.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, CIA experts thought they understood the techniques necessary for "breaking" a person. Under a strict regime of behavioral conditioning, "the possibility of resistance over a very long period may be vanishingly small," several researchers concluded in an analysis used in the CIA's 1963 manual Counterintelligence Interrogation. At the agency, pressure increased to field-test coercive interrogation tools. The task, as CIA second-in-command Richard Helms urged, was to test the agency's techniques on "normal" people.

At times, this imperative made the agency reckless. As part of the now notorious MK-ULTRA program—"one of the seamiest episodes in American intelligence," according to journalist Seymour Hersh—the CIA set up a safe house in San Francisco where its agents could observe the effects of various drug combinations on human behavior. They were in search of a "truth serum" and thought LSD might be it. Prostitutes were hired to bring unwitting johns back to the house, where the women slipped acid and other strong psychoactive substances into the men's drinks. From behind a one-way mirror, investigators watched, notebooks and martinis in hand.

Sometimes the men took the drugs and managed to carry on. Sometimes they babbled or cried. An internal CIA review condemned these high jinks in 1963, but Congress didn't investigate them until 1977, after a post-Watergate crisis of confidence in the agency.

At least officially, the CIA ended its behavioral science program in the mid-1960s, before scientists and operatives achieved total control over a subject. "All experiments beyond a certain point always failed," an operative veteran of the program said, "because the subject jerked himself back for some reason or the subject got amnesiac or catatonic." In other words, you could create a vegetable or a zombie, but not a robot who would obey you against his will. Still, the CIA had gained reliable information about how to derange and disorient a person who was reluctant to cooperate. An enemy could quickly be made into a confused and desperate human being.

sfux - 18. Nov, 07:57 Article 7496x read