Irena Sendler saved 2,500 Jewish children from the Holocaust

On the very day she died, a school in Warsaw was to be named “Irena Sendler’s Middle School No 23” and a ceremony occurred timely. Only her portrait was adorned by a black ribbon and so the school’s banner, as students and teachers stood silent with tears in their eyes. Her funeral, on May 15, brought together hundreds of people, friends and admirers of Mrs. Sendler from Poland and from abroad. On that day, AP reporter Monika Scislowska reported: “Pallbearers carried Sendler’s coffin through the historic Powazki cementary. More than 40 children from the newly named Irena Sendler Middle School in the capital’s Praga neighborhood looked on, each holding a yellow tulip…Frederic Chopin’s ‘Funeral March’ was played as Sendler was laid to rest and mourners gathered to hear a Catholic prayer.”

Mother of the ghetto children: Irena Sendler

“Jewish community leaders, Holocaust survivors, government ministers and the Israeli ambassador to Poland joined hundreds of other mourners in bright sunshine at Warsaw's Powazki cemetery to pay tribute to Sendler's life and achievements,” wrote Reuters Gareth Jones.

"Poland, the Jewish people, the world has lost a person who simply fought her whole life... for what it means to help another person, fought for never being indifferent, for never dividing humanity but bringing it together," Michael Schudrich, Poland's chief rabbi, told Reuters at the funeral.

A Kadish prayer was also sung by a rabbi in Warsaw, and Max Zinger from Canada, one of the readers of Ha’aretz daily online posted his own Mourner’s Kadish for her, entitled “We Lost a Great Human Being, an Angel!”

Mother of the ghetto children

Who was Irena Sendler? For 60 years of her life in Poland, she was a “no-person,” a humble social worker, a mother and wife, who never publicly admitted to heroic deeds during the war.Irena Sendler was born in Warsaw in 1910, the only child of a Polish doctor Stanislaw Krzyzanowski. Later they lived in Otwock, a near by town, where her father had a reputation of the only doctor who would treat Jewish patients during typhoid epidemic. He himself died of the disease in 1917. Irena was brought up as a Catholic. But unlike other Polish children, she was not biased against Jews and she was allowed to play with Jewish children.

Later she recalled that her father had taught her that “people can only be divided into good or bad; their race, religion, nationality don’t matter.” She was true to these principles for the whole life. She studied law and pedagogy. During her higher studies in Warsaw, she opposed discrimination against Jews and defended her Jewish colleagues. Before the outbreak of the war, she married Mieczyslaw Sendler and became a professional social worker, caring also for poor Polish and Jewish families in Warsaw. Under the German occupation Mrs. Sendler began to help Jews from the very fall of Poland in September 1939. In 1940, over 400,000 Jewish citizens living in the Warsaw ghetto were sealed off behind high walls. Jews leaving the ghetto without a German permit were punished by death, and the Poles were strictly forbidden to help Jews in any way. If caught, such persons and their household members faced immediate death sentence. Nowhere else in the German-occupied Europe, but only in Poland, Nazi rules were so brutal.

In spite of the great danger, Irena Sendler, a 29-year-old wife and mother and some of her colleagues decided to help Jews. They obtained special passes from the city authorities, letting them visit the ghetto as sanitation workers. They could carry food, clothes and medicine, especially typhoid vaccines, to the walled-off part of Warsaw. Sendler, together with her friend and co-conspirator Irena Shultz and other social workers, rescued Jewish babies, children and youngsters from an inevitable death in the Warsaw ghetto or in German concentration camps.

The most difficult was to persuade Jewish parents, mothers in particular, to hand over their beloved children to merciful gentiles who wanted to save them: “…infernal scenes. Father agreed but mother didn’t. Grandmother cuddled the child most tenderly and, weeping bitterly, said ‘I won’t give away my grandchild at any price,’” Mrs. Sendler later recalled. The helpers came back to Jewish homes several times, occasionally finding that the families living there were gone through the infamous Umschlagplatz, a railway platform from which Jews were loaded into cattle-cars to be deported to Treblinka and to other death camps. About 20 Polish social workers led by Mrs.

Sendler exposed themselves to immediate capital punishment but carried on, using all kinds of tricks to get children out of the ghetto walls. Smuggling of them out was highly risky and it also had to involve dozens of people inside the ghetto and hundreds outside, on the so called “Arian” side of Warsaw. Inside the sealed-off “Jewish City” the social workers wore Star of David, same as the Jews, not to call attention of Germans and also to show their solidarity with the persecuted people.

They smuggled babies and small children in wooden boxes, wrapped in packages, getting them out in ambulances and trams, carrying them through holes, sewages or even through corridors of an old courthouse leading out of the ghetto to the other side of the city. One small boy, Stephan, got out under a man’s coat, with his feet in the man’s shoes and hands clasped on his belt. Some children were rescued in coffins, pretending to be dead, other were hidden in suitcases.

But the mortal danger didn’t stop beyond the ghetto walls, as Germans and some Polish traitors could locate a Jew anywhere, and as helping Jews meant immediate death to the helpers and their families. Jewish babies, children and youngsters saved from the Warsaw Ghetto received false Christian identity documents and were hidden in orphanages, convents, parish rectories and with Polish foster families. Jewish teenagers joined guerilla units and fought against Germans.

Irena Sendler began helping Jews immediately after the German invasion of Poland (September 1939). But only in December of 1942 her team of about twenty social workers received substantial support from a newly found Council for Aid to Jews, codenamed “Zegota” (and old Slavonic first name, unrelated to Jewishness).

Zegota, a codename for the Council for Aid to Jews, operated underground from 1942 to 1945, under the auspices of the Polish Government in Exile to help the Jews and find, for at least some of them, a place of safety in occupied Poland. The organization helped to save many thousand Polish Jews by providing relief money, false identity documents and shelter. “Zegota as an organized effort was tantamount to ‘Schindler’s List’ multiplied a hundredfold,” said Professor Zbigniew Brzezinski.

Irena Sendler became head of Zegota Children’s Section which cared for 2,500 of the 9,000 Jewish children smuggled from the Warsaw ghetto. This unique organization, the only one in the German-occupied Europe, not only helped Jews in Poland but also assured that the saved children, when the war was over, must be returned to their Jewish relatives or communities. Thinking of their future, Mrs. Sendler carefully noted the true names of “her” children and kept slips of papers at home.

In the hands of Gestapo

On October 20, 1943 eleven Gestapo officers came to Sendler’s home to arrest her. She managed to pass the slips to a friend, who hid the paper in her stockings and later buried the “archive” in glass jars under an apple tree in an associate’s yard. Some 2,500 names of Jewish children were thus recorded and saved.

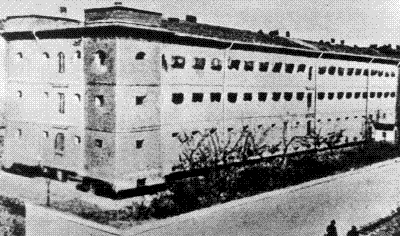

Pawiak Prison: Her name was listed on German public bulletins as among those executed in early 1944.

Irena Sendler was taken to a notorious Pawiak Prison, which few people left alive. She spent there three long months. Beaten and tortured repeatedly, with both her arms and legs broken, she revealed nothing. “I kept silent. I preferred to die than to reveal our activity,” she was quoted as saying. While in prison, she was sentenced to death for helping Jews. The worst moment of the brutal interrogation happened when a Gestapo officer, questioning her, showed a thick file with information from Polish denunciators. She survived three months in jail and was set free by a Gestapo officer, who took a huge bribe from Zegota to check off her name on a list of those already shot.

Her name was listed on German public bulletins as among those executed in early 1944. Until the end of the war she had to live in hiding, under a false name. Even then, she continued her work, endangered by Germans but also by Poles. In 1944 (according to a Polish weekly “Wprost”), an intelligence unit of a Polish nationalist and anti-Semitic underground organization NSZ issued a death sentence on her as an alleged “Communist and Jew-helper.” Mrs. Sendler avoided having been shot by her compatriots but suffered pain until the end of her life, after the Gestapo thugs beat her up and broke her arms and legs. Never again would she be able to walk without crutches.

Forgotten in Communist Poland

After the end of the war (1945) Irena Sendler divorced her first husband (though she is known under his family name) and married a fellow conspirator Stefan Zgrzembski. They had two sons and a daughter. One died a few days after birth. The second son, Adam, died of heart failure in 1999. (She is survived by a daughter, Janina Zgrzembska, and a granddaughter.)

Her life in Communist Poland was not a happy one. In 1949, she was brutally interrogated by the then Communist security service (UB) for allegedly hiding members of Polish underground organization (AK, Home Army). She lost her baby after that. Before, she managed to hand over her “jar archive” with 2,500 names of the Jewish children her team had saved to Adolf Bermann, the chairman of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland. Under German occupation, “Zegota” included Jewish organizations, represented by Adolf Bermann and Leon Feiner. The Council for Aid to Jews “Zegota” was the only underground organization that was run jointly by Jews and Polish gentiles, representing a variety of political movements. They helped at least 4,000 Polish Jews, mainly in Warsaw, and both the Polish and the Jewish underground was able to reach with aid to some 8,500 of the 28,000 Jews hiding in Warsaw, and to about 1,000 trying to survive elsewhere in Poland.

After the war, Irena Sendler continued her work as social welfare official and director of vocational schools but she and her family couldn’t avoid harassment from the then Communist authorities. She never spoke in public about her wartime heroic deeds, having chosen a private life, dedicated to her family and friends. The memories of the past haunted her. As Mrs. Sendler recalled later, she and her co-workers visiting the Warsaw ghetto saw starving children, abandoned corpses and Nazi SS officers using skulls for target practice – “I saw all this and a million other things that a human eye should never have to see” she later said, “and it has stayed with me for every second of every day that God granted me to live.”

The Polish Communist authorities were not interested to reward her for the help rendered to Jewish children during the war. But the Jews did not forget. In 1965, Irena Sendler became one of the first “Righteous Gentiles” honored by the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem for wartime heroics. Polish authorities did not allow her to go to Israel to be praised there. Only in 1983, she could collect the award (a medal “Righteous among the Nations”), confirmed by the Knesset. In 1991, she became an honorary citizen of Israel.

Earlier, in 1968, when the Communist authorities cracked down on Polish Jews, calling them “Zionists” and expelling some 20,000 from Poland, Mrs. Sendler announced she was ready to hide Jews again. For her statement, the authorities expelled her children from the Warsaw University.

In Communist Poland, official statistics (backed by Dr. Szymon Datner of the Jewish Historical Institute) listed the total number of Jewish children saved during the war as 500 – 600. Only in March of 1979, a joint declaration issued by the surviving members of the wartime Warsaw City Department of Social Care and the Council for Aid to Jews “Zegota” (signed by Irena Sendler, Jadwiga Piotrowska, Izabela Kuczkowska and Wanda Drozdowska) brought up that number to about 2,500. Records show that Sendler’s team of about 20 people saved so many Jewish children between October 1940 and the final liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto in April 1943, when the Nazis, furious because of the Jewish unexpected armed resistance (Ghetto Uprising ‘43), burned and demolished the Jewish quarter of Poland’s capital, shooting the surviving residents or sending them to death camps.

In spite of the fact that already in 1958 Irena Sendler was rewarded by “In the Service of Health” medal from Poland’s Minister of Health, she never became a publicly renowned person for her outstanding bravery and dedication in the Second World War. This situation lasted throughout the years of People’s Poland (the Communist regime ended in 1989). In 1989, she was 79, ill and forgotten. This situation lasted until 1999, when four curious American high-school students from Kansas caused a big change in her life.

From the shadows to world fame

Irena Sendler’s life-story is so fascinating that millions of people everywhere read and write about her deeds now with true admiration. While writing this article, I have put “Irena Sendler” on my browser finding more than 440 thousand hits (about 226,000 in English and over 41,000 in Polish). But until 1999 there were only a few remarks on her heroic life in the media and on the Web. One of them drew the attention of a history teacher from a high school in Uniontown, Kansas in the United States.

Norm Conard showed a short clipping of the March 1994 News and World Report weekly to four of his students, all girls -- Megan Steward, Elisabeth Cambers, Jessica Shelton and Sabrina Coons -- asking them to do some research on the news which said ’Irena Sendler saved 2,500 children from the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942-43,” in their year-long National History Day project. At first, both the teacher and the students thought it was a typographical error, since no one of them heard of this woman or her story. “It might be a mistake,” Mr. Conard told a Polish “Dziennik” daily in May 2008, “perhaps there were 25 children saved, or 250 at most?”

But the information proved true and that Polish woman, supposed to be dead for years, turned out a living and the most interesting witness.

The wartime story of Irena Sendler was not fully known to the American girl-students at the time they wrote a scenario of a short drama, entitled “Life in a Jar.” Their presentation enjoyed an enormous success and it was played over 240 times all over the United States and in Europe as of May, 2008. The performance brought a great popularity to the “Mother of the Children of the Holocaust.” But it also helped the young authors and actors to come over to Poland (in 2001 for the first time, and later in 2002 and 2005) to meet their heroine.

A long-time cordial correspondence developed between Megan, Elisabeth, Jessica and Sabrina from Uniontown and Irena in Warsaw, with a translation help from a Polish student, Anna Karasinska, from a local Kansas college. Mrs. Sendler wrote to them in one letter “…Before the day you had written ‘Life in a Jar’, the world did not know our story, your performance and work is continuing the effort I started over fifty years ago, you are my dearly beloved girls.”

Thank to the four curious girls from Kansas and their presentations of “Life in a Jar”, Irena Sendler was finally rediscovered in her own country, Poland, and in 2003 she was rewarded by the highest civilian decoration, the Order of White Eagle, then honored by the Polish Senate.

In 2003, she was also honored in America by the Jan Karski Award “For Valor and Courage” ($ 20,000). On that occasion, John Paul II sent to Mrs. Irena Sendler a following letter:

The Vatican, November 13, 2003 – from POPE JOHN PAUL II – TO IRENA SENDLEROWA:“Honorable and dear Madam. I have learned you were awarded the Jan Karski prize for Valor and Courage. Please accept my hearty congratulations and respect for your extraordinarily brave activities in the years of occupation, when –disregarding your own security – you were saving many children from extermination, and rendering humanitarian assistance to human beings who needed spiritual and material aid. Having been yourself afflicted with physical tortures and spiritual sufferings you did not break down, but still unsparingly served others, co-creating homes for children and adults. For those deeds of goodness for others, let the Lord God in his goodness reward you with special graces and blessing. Remaining with respect and gratitude I give the Apostolic Benediction to you.” Signed: Pope John Paul II

In 2005, a book by Anna Mieszkowska called “Mother of the Children of the Holocaust. The Irena Sendler Story” was first published in Polish and later on translated to Hebrew, German (2006), and in part to English as a 23-page pamphlet. Several TV documentaries about her life have been produced in Poland and abroad. After she became a honorary citizen of Israel (1991), in 1995 she was interviewed on camera in a 40-minute French documentary by Polish-born Franch writer and film-maker, Marek Halter: “Irena Sendler, her squinty, blue eyes awash with tears, recounted how she smuggled Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto in an ambulance. In a front seat, a dog barked loudly to drown out the cries of her small passengers. Still visited by some of the Jews she saved, “I could have done more,” she said. “This regret will follow me to my death.”” (AP reported)

“It took a true miracle to save a Jewish child,” Elzbieta Ficowska, who was saved by Sendler’s team as a 5-month-old baby in 1942 and is a chair-woman of the Association of the Children of the Holocaust now, recalled in an AP interview in 2007. “Mrs. Sendler saved not only us, but also our children and grandchildren and the generations to come,” she concluded.

In 2007 Irena Sendler was nominated to Nobel Peace Prize by efforts of President of Poland Lech Kaczynski and many other people in Poland and abroad. She lost to Al Gore, former Vice President of the United States, but she didn’t care about it. When she heard the news, Irena Sendler told her doctor, Hanna Wujkowska, that she was relieved. For her the greatest “Noble Prize” were letters from children of Poland and the world, because there were schools named after her in many countries and she received letters with photos of children – for them she is somebody they could follow.

In 2008, before her 98th Birthday (Feb.15), students from Kansas working on The Irena Sendler Project wrote on their Web site: “she is still in good health and continues to inspire many. Her family and many of her saved children continue to tell her story of courage and valor.” But already in April Irena Sendler fell ill (of pneumonia) and on Monday, May 12, she passed away at 8.00 a.m. CEST in a Warsaw hospital. Her funeral was arranged in Warsaw on May 15, 2008 – three months after her last Birthday.

During a memorial ceremony at Ford Scott in Kansas somebody wrote “…Her legacy of repairing the world continues, as good continues to triumph over evil.” On May 13, a day after her death, the Hallmark Hall of Fame in the U.S.A. announced that a movie based on Mieszkowska’s book was being prepared and will be filmed in Poland and aired by CBS. John Kent Harrison wrote the script and will direct it.

One year before her death, Irena Sendler wrote in a letter to the Polish Senate: “Every child saved with my help and the help of all the wonderful secret messengers, who today are no longer living, is the justification of my experience on this earth, and not a title to glory.”

This sentence might be the best epitaph for Mrs. Sendler, Mother of the Children of the Holocaust, an Angel in the Ghetto as many people used to call her.

© David Dastych 2008

sfux - 26. Mai, 08:52 Article 23916x read